A Life-Changing Sabbatical

Sabbaticals are a gift to ministers in the United Reformed Church. They come every ten years to help minsters rest, reflect, pray and seek God. They consist of taking three months out from regular ministry, working with a sabbatical supervisor and synod training officers to make the most of the time. The break is seen by many ministers as life-giving, refreshing and even essential to ongoing ministry.

This is the story of my life-changing sabbatical…

by Geoff Felton, Moderator of the United Reformed Church Mersey Synod

It was my privilege to explore the transatlantic slave trade and the work that goes on today to bring end modern slavery. I examined the Church’s role in the slave trade both historically and today.

Starting in my home city of Liverpool, I explored the history of the city and discovered road names, buildings, schools and parks all with links to historic slavery. Laurence Westgaph, a Liverpool historian, says ‘If you scratch Liverpool it bleeds slavery.’ The civic authorities in Liverpool have worked hard to recognise the role of slavery in the construction of the city, realising that Liverpool’s phenomenal growth during the 17th and 18th centuries was due to the role the city played in bringing misery to so many people’s lives.

Despite this, the slave trade is still active today. The UN estimates there are 52 million people held in various forms of bondage against their will. Modern-day slavery is a wide-ranging description and includes practices such as debt bondage, domestic servitude, sex work and enslavement in call centres.

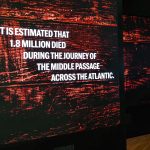

Between the early 1500s and mid 1800s it’s thought that at least 12.5 million people were transported from West Africa across the middle passage to the new world. Approximately 1.5 million were transported on ships with links to Liverpool. By 1740 Liverpool had replaced Bristol as the dominant British port in the development of the slave trade.

The year 1807 saw the official abolition of the slave trade in the British Empire. The practice did however continue and it wasn’t until 1840 that most enslaved people in the colonies were released from their ‘apprenticeships’ – this at the cost of £20m compensation to the slave owners, a debt that was only paid off by the UK government in 2015.

Jamaica

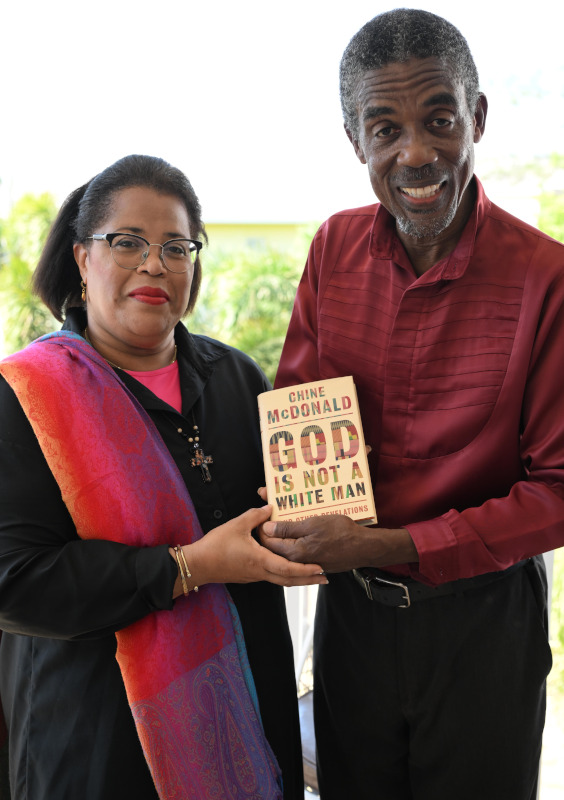

My next stop after Liverpool was Jamaica, where I joined a group from the URC, the Church of Scotland and Christian Aid to deliver an apology from the URC for its historic links with the slave trade and to explore the legacies of the transatlantic slave trade on communities and individuals in Jamaica. Much of this time was taken up meeting activists calling on the UK government for reparations. I met with politicians, community activists, church members and historians all involved in the call for reparative justice.

At the forefront of the fight for justice was the United Church of Jamaica and the Cayman Islands working in partnership with the Churches Reparations Action Forum (CRAF). The CRAF has set out a seven-point plan for the introduction of reparative justice that goes beyond financial assistance and extends to addressing the deep-seated roots of injustice that have sprung from the slave trade. The plan involves the creation of schools that will teach history, new free villages established on land gifted by the Church to help settle landless persons and promote a culture of community openness to training and empowerment.

My time in Jamaica was eye-opening and made me see the active participation of the Church in the areas of injustice and poverty. I was introduced to abolitionists from the past who engaged in small acts of civil disobedience in order to bring an end to the trade in human beings.

Charleston

From Jamaica I journeyed on to Charleston, South Carolina, in the USA. Charleston was responsible for importing more people to the USA from West Africa than any other port on the west coast. On the surface, Charleston appears to be a sleepy, historic town with chocolate box houses and a sunny outlook. Its history however is marked with oppression and injustice. While there I visited the old slave market which brought the sale of human beings indoors because it was felt that selling people on the open streets didn’t fit the image the city leaders wished to convey.

A guided walk took me around the city and pointed out places of note, including the harbour, homes and shops where the fight for freedom took place, and churches built on the profits of the trade in human beings.

Charleston is home to the International African American Museum, a place replete with information about the transatlantic slave trade and the impact it has had on American culture and life. The museum was full of school groups learning of the history of the city, the slave trade of the past and how America’s culture has been shaped by it. It was a sobering experience to walk amongst the exhibits and try to gain a perspective on the enormity of the slave trade.

My final visit in Charleston was to the Magnolia Plantation. An old open air museum with a huge stately home and beautiful gardens including alligators, this venue was established on the back of the slave trade and workers made the estate what it is today. The owners of the estate have tried to acknowledge the history by preserving the homes of the enslaved and providing a guided walk looking at what life was like for them. While being a worthwhile trip, it did feel as if the acknowledgment of slavery in its past was simply a bit of an afterthought.

Ghana

My final journey took me to Ghana to work with the Presbyterian Church of Ghana and to visit the area where many of those sent to the Americas originally came from.

Ghana is full of history and the nation has sought to come to terms with its past and the role it played in the slave trade. I visited the slave castles and saw how the trade in people evolved from raw materials to human beings. The original dungeons in the slave castles such as Elmina were meant for products such as coffee and sugar cane but when the trade in human beings became more lucrative the dungeons were turned over to the storage of people. What this showed me profoundly was the commodification of people in the slave trade. People were seen as goods to be traded not as human beings with inherent worth and dignity. One of the sad things about this was the dungeons were located below the chapels where the residents worshipped every Sunday and from where the cries of the enslaved could be heard during worship.

Ghana is a nation that has wrestled with its history, partly because of its complicity in the slave trade but also because it has been abused and exploited by many nations including Portugal, UK and the Netherlands. The Church is at the forefront of fighting the continuing plague of slavery that exists in Ghana today, largely as child labour on Lake Volta. While in Ghana I visited the offices of International Justice Mission and heard stories of how they had been involved in bringing to safety significant numbers of young children who had been trafficked to the lake largely by trusted family members.

Ghana seems to be a nation where the church is at the forefront of bringing hope to people’s lives who are trapped in poverty, slavery or for whom there seems to be no hope of employment or a worthwhile future.

Sabbatical learning

Humanity and kingdom

During my visit I recognised two inescapable facts: the Church played a significant role in the trade in human beings and the New Testament is silent on the ownership of enslaved people. As I considered slavery and the way it was worked out both historically and today, I have asked: how can a person do such a thing to another human being? I have come to two conclusions.

The Christian story is one of relationship: God as Trinity, in relationship with God’s very self, humanity in loving relationship with each other, and God’s perfect relationship with humanity. Genesis declares that each person is created in the image of God and is of intrinsic worth, not because of status or wealth but because of the identity conferred on them by God. This has always been a radical idea. Plato, for example, believed in a hierarchical structure to society with the wise and good at the top and with women, slaves and children lower down the pecking order. He believed if you like, in a natural inequality, an ideology reflected in the culture of his day.

Early in the book of Genesis we discover the relationships between humans, and the relationship between humans and God is broken and not as it is intended to be. Created in the image of God, humans are intended to live in perfect relationship with each other and with their creator. Brokenness, however, leads to damaged relationships that can lead to oppression and harm.

When we lose sight of our shared humanity, created in the image of God, we dehumanise one another and no longer see the humanity in our existence. Enslavement and genocide require dehumanisation. It is only when we separate the other from their humanity that we can treat each other with such disregard.

Katherine Gerbner in the book Christian Slavery: Conversion and race in the Protestant Atlantic world suggests the role of the early missionaries to the Caribbean was not to do with emancipation and abolition but it was driven by identity. The early missionaries focused on convincing the authorities, both civic and religious, that black people could convert to Christianity because they were indeed human beings!

So the first way I believe people can hold others in captivity is by denying their humanity. The second reason is less nuanced.

In the slave castles of Ghana, the dungeons built for products such as coffee and sugar cane, but were reassigned to hold people when that became more lucrative. I’d suggest the second reason people could enslave others was greed. The plantations in the Caribbean and Eastern USA were centres of wealth and finance. The enslaved generated wealth by producing materials for trade. Modern stories of the enslaved point to economic reasons. The problem is still alive in our world today. Whether it is young boys being kept illegally on the fishing boats of Lake Volta or families held against their will in the brick kilns of Tamil Nadu, they finance those wishing to increase their wealth and status.

Dehumanisation and greed are sin. The brokenness of our world is caused by sin that manifests itself in many different ways. The enslavement of human beings is an obvious outworking of sin in our world, but sin manifests itself in more subtle ways in all our lives.

If the problem is sin, then a purely economic or educational solution to the difficulties of enslavement will always fall short because it does not deal with the root of the problem. As Christians work towards justice, mercy and compassion, they hold out an offer of healing and restoration, not just the result of hard work, but the deep soul-healing that come through a restored relationship with our creator and with one another.

This restoration I believe is why Jesus came to earth. He ushered in the Kingdom and brought forgiveness and healing. The charge he leaves the church, is to point to the King and do the Kingdom work of seeking justice and seeing people set free from all forms of slavery

Justice

‘Righteousness and justice are the foundation of your throne; love and faithfulness go before you.’ Psalm 89:14

‘For Christians living in a relatively affluent and orderly civil society, this act of remembering the injustice and abuse in the world is not an easy one. But it is not a new challenge either’. – Gary Haugen

When reading the Bible, it doesn’t take long to discover that justice is a fundamental characteristic of God. The theme of justice is woven throughout the Old Testament and when Jesus arrives in the New Testament the theme of justice is implicitly related to the Kingdom of God.

Christians pray ‘Thy Kingdom come’, but what does that mean and what does the incoming of the Kingdom look like?

In Matthew 20, Jesus tells the story of the workers in the vineyard and shows the Kingdom of God and justice go hand in hand together. Jesus’ manifesto in Luke 4 points to freedom not captivity, and justice not oppression.

Slavery is counter to the Kingdom of God. Individuals being held in enforced servitude are held captive against their will and treated as commodities to be bought and sold. If the kingdom of God is to be evident then justice must be done and the enslaved set free.

Pope Francis says that in Scripture ‘justice is not an abstraction or a utopia. In the Bible, it is the honest and faithful fulfilment of every duty towards God; it is to fulfil his will.’

I believe the issue of enslavement is tied together with seeing the oppressed set free and the inbreaking of the Kingdom of God. If we as the Church are to represent the character and family of God then we are to fight for justice and release for those who are enslaved. Living for God means seeking the Kingdom first and letting go of our own agendas and priorities.

The number of people held in modern slavery is daunting so what can the church do about it?

First, pray. In the face of the growing trade in enslaved people we are called to pray for wisdom and discernment. What is God calling us, as the people of God, to do and be?

Second, advocate for those without a voice. The job of today’s abolitionist is not a moral one where we argue the rights and wrongs of slavery, it is an educational one, to let others see that this wickedness continues all over the world. It is to remove the blinkers from the comfortable so we may see the extent of the industry in human trafficking.

Third, partner with those who are involved on the frontline of rescuing and restoring enslaved people. Organisations such as International Justice Mission provide specialist skills to investigate, release, prosecute and rehabilitate in cases of enslavement. They have resources to help in the fight against slavery and can provide speakers to speak at your events.

Hope

In all I was exposed to, it would have been easy to be overwhelmed by the enormity of what I saw and read. I do believe however there is one last theme that needs to be explored.

When we become overwhelmed, a darkness descends and it can feel like all hope is gone. The people I met and the stories I heard during my sabbatical gave me hope for the future.

The Church is a living community all over the world and while it has to address significant failings, it is a beacon of light that stands in a dark world for what is good and lifegiving. Christ draws us together from across all cultures and nations to offer hope to the world.

The Church manifests the Kingdom of God through its search for justice, its gathering together to worship and its fight to see people set free and released from bonds both literal and spiritual that enslave them.

During my three months I encountered many people fighting the injustices of today. Most of them are quite ordinary people doing ordinary things but with an extraordinary vision that God wants to use them to bring about release, healing and deliverance. Whether it’s an Anglican in Liverpool, a United Church member in Kingston, a Presbyterian in Accra or a member of International Justice Mission on a Zoom call, the unity we have in Christ compels us to reach out to the those victims of injustice and reflect the character of God and his justice into his world. God is at work and there is no stopping him.